The International Family Law Group LLP represented the applicant father in his application seeking the return of his daughter from a non-Hague country, in a case that has been reported as Re A (A Child) (Removal to non-Hague country) [2023] EWFC 330 and Re A (A Child) (Removal to non-Hague country) (No 2) [2024] EWHC 2016 (Fam). The case was heard by Mr Richard Harrison KC (sitting as Deputy High Court Judge, as he then was) at The Royal Courts of Justice. His two judgments have since been placed in the public domain:

- [2023] EWFC 330: https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWFC/HCJ/2023/330.html

- [2024] EWHC 2016 (Fam): https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Fam/2024/2016.html

James Netto of The International Family Law Group initially represented the applicant father on a pro-bono basis through the Duty Advocate scheme run by the Child Abduction Lawyers Association (CALA). Another solicitor assisted the mother. Mr Richard Harrison KC comments in his judgment: ‘I am enormously grateful to these highly skilled and specialist lawyers for the assistance they are willing to offer, free of charge.’

Mr Richard Harrison KC further praised the legal representatives in his second judgment stating: ‘the court has been enormously assisted by the fact that each of the parties has been represented by expert solicitors and counsel’.

Background

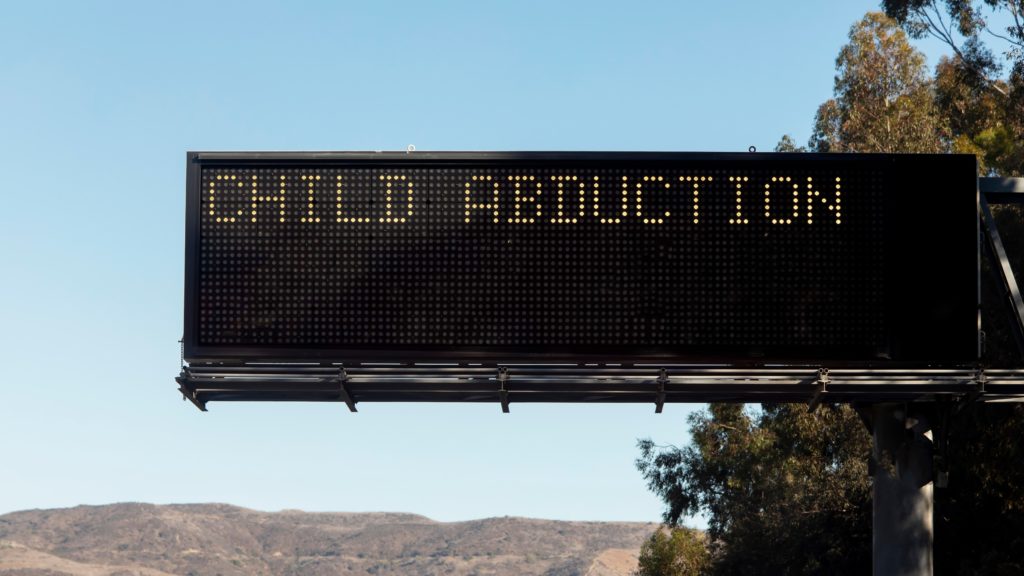

The background facts to this case have been described as ‘highly unusual’ in the judgment. The father holds both the nationality of ‘country X’ and of the UK. The mother is a national of ‘country X’. The father has chronic renal failure and is on a waiting list for a kidney transplant; he undergoes dialysis several times a week. The parents first met in country X in 2012, married in 2015 and their daughter, referred to as A in the judgment, was born in January 2017 in country X. When A was 8 months old, she and her mother moved to England to join the father, who had continued to live in England throughout the parents’ relationship. In October 2019, the parties separated and all contact between A and the father ceased. In August 2021, the mother took A to country X without the knowledge or consent of the father, leaving A under the care of the maternal grandmother. As such, this case was unusual because there was no one with parental responsibility residing in the country that A had been abducted to.

The father only became aware that the child had been taken to country X in December 2022, when the mother informed the West London Family Court of the same in the course of proceedings relating to the father’s application for a child arrangements order. The father subsequently applied to the High Court for an order for the return of A from country X to England. He was acting in person at the time. Initially an order was made for A to be summarily returned to the UK under the 1980 Hague Convention. This order was subsequently set aside by Mr Justice MacDonald in July 2023 on the basis that country X was not a signatory to the 1980 Hague Convention. The case was then referred for a two-day hearing to consider the father’s application for the return of A under the inherent jurisdiction.

The mother’s case centred around financial difficulties and her pursuit of a nursing qualification. She claimed that after being required to leave the father’s home, she was unable to manage financially. She argued that the only option was for A was to stay with the maternal grandmother in country X whilst she completed her studies. The mother believed that by 2025, once she had completed her nursing qualification and was able to secure a full-time job, she could return to England and care for A. The mother also raised concern about the father’s alleged cannabis use and domestic abuse, presenting these as factors contributing to her decision to take A to country X.

The father denied the allegations of domestic abuse and instead argued that the mother had prioritised her education over A’s welfare. He contended that the mother’s actions had severed his ability to have a meaningful relationship with A, which he felt could not be met through video contact alone. Additionally, the father expressed concerns about his own health, as he was awaiting a kidney transplant, further complicating his ability to maintain contact with A.

After hearing the entirety of the evidence at the hearing in September 2023, including oral evidence from the Cafcass officer, the Judge determined that further investigation was necessary before a decision could be made regarding A’s return. The Judge ordered the appointment of a Guardian to represent A’s interests and a final hearing was listed for early 2024.

At the final hearing in February 2024, the substantive issue before Mr Richard Harrison KC concerned the date of A’s return to the UK and the mechanism by which that should be achieved. Ahead of the hearing, the mother amended her position, stating that A would not be able to return to the UK until the summer of 2026, citing her inability to secure a full-time nursing person until after September 2025.

The judge considered the current living situation in country X, where A was performing well at school, and enjoying life with her maternal grandmother. However, the judge also recognised that A’s time with her parents was severely limited, and the ongoing separation was harmful to A’s relationship with both parents.

After reviewing the evidence, the judge concluded that the uncertainty surrounding the mother’s work schedule and her plans for A’s return made it impossible to determine with confidence whether a return in 2025 was feasible. As a result, the judge adjourned the case and set a review hearing for early 2025. It is unusual for abduction proceedings to be adjourned for almost 12 months, given that return orders are usually sought on an urgent basis. However, the specific and unique circumstances of this case led the Judge to conclude that such an adjournment was necessary in order to determine both the welfare implications and the practicalities of any return date ordered.

The Law

If a child is abducted from this jurisdiction to a 1980 Hague Convention country, then there is a clear international framework is in place to assist with the swift return of the child, although of course enforceability issues may arise in some cases. It can often be more challenging to secure the return of a child to a non-Hague convention country where there are no international treaties that can be relied upon to secure a swift and summary return. However, it is still possible for the English court to make orders under the inherent jurisdiction to assist with the return of children who have been abducted to a country that is not signatory to the 1980 Hague Convention. When determining whether a child should be returned from a non-Hague Convention country, the court will be guided by welfare principles. Given that country X in this case is not a party to the 1980 Hague Convention, the question for the Judge to determine was whether it was in the child’s best interests to return to this jurisdiction.

The judge referred to the factors outlined in Re NY [2019] UKSC 49 [paragraphs 56 to 63], which established key considerations in cases involving international child abduction, when the Hague Convention does not apply, namely:

- Whether the evidence before the court was sufficiently up to date to make a summary order for the child’s return;

- Whether sufficient findings had been made to support the summary return order;

- Whether an enquiry should be conducted into any or all of the aspects of welfare specified in section 1(3) of the Children Act 1989 and, if so, how extensive that enquiry should be;

- Whether the disputed allegations of abuse needed further investigation, and if so how extensive that enquiry should be;

- Whether a return order would be appropriate without information about the child’s current arrangements in country X;

- Whether, considering the above, oral evidence should be given by the parties and, if so, upon what aspects and to what extent;

- Whether the court should have considered if a Cafcass report should be prepared and, if so, upon what aspects and to what extent should be explored; and

- Whether the court needed to assess the relevant abilities of both jurisdictions to reach a resolution of the substantive issues between the parties, and to satisfy that the court of the other jurisdiction has the power to authorise a relocation.

The judge also acknowledged that, despite the application being made under the inherent jurisdiction and having considered the factors in Re NY, a full welfare analysis was necessary in light of the limitations in the parents’ evidence, the length of time A has been in country X and the difficult nature of the balancing exercise which needed to be undertaken by the court.

Additionally, the judge additionally made reference to Section 2A of the Family Law Act 1986 and Lachaux v Lachaux [2019] EWCA Civ 738, concluding that the court had jurisdiction to make a welfare order ‘in connection with‘ the divorce proceedings that have concluded between the parties. This made it possible for the court to address the issues related to A’s best interests in the context of the ongoing family dynamics.

Conclusion

The judge’s careful and nuanced approach to this case shows the care required when handling cases of complex international child abduction, particularly when the country involved is not a signatory to the 1980 Hague Convention. In this case, it was ultimately agreed that the child should return to this jurisdiction. However, the date for return remains a disputed issue that is yet to be determined by the court. Until the date of return, the child shall travel to England to spend time with the father.

The judge’s approach highlights the importance of considering all options carefully and ensuring that decisions made about a child’s welfare are fully informed by the evidence available. It also serves as a warning to seek specialist legal advice at the outset in matters of this nature. In cases of international child abduction that fall outside of the Hague Convention, the court must not only assess the best interests of the child but also the practical realities of any potential solutions. The case is a reminder of the complexities involved in cross-border family disputes and the need for thoughtful, case-specific solutions that prioritise the well-being of the child.

Partner, James Netto, Associate, Rosa Schofield, and Paralegal, Beatrice Holt, represented the father in this matter. Tadhgh Barwell O’Connor of 1KBW was instructed at the final hearing.

Beatrice Holt

[email protected]

The International Family Law LLP

www.iflg.uk.com

© March 2025

- Beatrice Holthttps://iflg.uk.com/blog/author/beatrice-holt

- Beatrice Holthttps://iflg.uk.com/blog/author/beatrice-holt